Soldiers, scouts, and the limits of persuasion

When Galileo pointed his telescope at Jupiter, he invited the scholars to look. Some refused. They already knew the answer—Aristotle had settled the heavens. Looking wouldn’t teach them anything. It would only threaten what they’d built their careers defending.

You’ve seen this. You point to Bitcoin. You explain what you see. And watch them refuse to look.

So you try harder. Better analogies. More patience. You assume the problem is knowledge, and knowledge can be transferred.

It doesn’t work. The curious stay curious. The dismissive stay dismissive. The energy spent on conversion produces nothing.

This is the trap: the belief that the right explanation will unlock understanding. That resistance is a puzzle you can solve with better arguments.

It’s not. Once you understand why, it changes where you put your energy.

Two mindsets

Julia Galef, in The Scout Mindset, describes two cognitive modes: the soldier and the scout.

Soldiers defend positions. Information is either ammunition or threat. New data gets evaluated by a single criterion: does this support or undermine what I already believe? Being wrong feels like defeat, so soldiers are motivated—usually unconsciously—to avoid it.

Scouts map territory. Information is data to be integrated. Being wrong is an update, not a loss—the map gets more accurate. Scouts are motivated to see clearly, even when clarity is uncomfortable.

These are modes we all move between, not personality types. But some people are in soldier mode on specific topics, and that’s where persuasion breaks down.

When you pitch a scout, you can feel it. They ask questions—real ones, not rhetorical traps. They’re testing their map, genuinely curious whether yours is better.

When you pitch a soldier, you feel that too. Objections that aren’t questions. Dismissals that come before engagement. The emotional charge that signals you’ve threatened identity, not just ideas.

The soldier isn’t evaluating Bitcoin. They’re dug in, defending something. Expertise that already answered the question of what money is. A public stance that would be embarrassing to reverse. An identity built on the current system working.

Whatever they’re defending, explanations can’t touch it. You’re having an argument about maps while they’re fighting a war about territory.

Intelligence doesn’t predict openness—if anything, the opposite. Smart soldiers have more resources for defense. More sophisticated arguments for why they’re already right. Credentials are the wrong filter for finding people who’ll listen.

Structural soldiers

Some soldiers aren’t just protecting ego. They’re protecting income.

Central bankers. Monetary economists. Financial journalists at legacy outlets. Institutional investors whose models assume fiat stability. These are the Cantillon winners—first in line when new money gets created. Their careers are fiat assumptions in practice.

For them, soldier mindset is economically rational. They’re being paid, literally, not to see what you’re showing them.

Timing won’t solve this. The standard marketing wisdom says “they’ll come around eventually.” But that assumes circumstances will reach them. Structural soldiers are insulated. Inflation doesn’t eat their savings the way it once ate yours. Currency crises don’t threaten their careers—their careers depend on managing those crises within the current paradigm.

Only losing the position itself would expose them. And that’s rare.

I stopped spending energy here. The incentives are structural—pushing against economics.

Time and energy are finite. Spending them on structural soldiers wastes both.

What creates scouts

If you can’t argue someone out of soldier mindset, what does?

Circumstances.

Inflation spikes. Bank failures. Currency crises. Institutional betrayal. Personal financial trauma. A job loss that reveals how fragile the system actually is.

These are the events that turn soldiers into scouts. Arguments don’t do it. Patience doesn’t either. Pain does.

At any given time, most people aren’t ready to hear what you’re saying. Not because they’re stupid—because nothing in their world has broken yet. They’re not evaluating alternatives because they don’t need alternatives.

People start looking when something in their world shifts.

For Bitcoin, that shift is usually painful. Nobody stress-tests their assumptions about money during the good times. The questions come when something breaks. When inflation eats their savings. When a bank freezes their account.

Those circumstances can’t be caused or manufactured. They happen on their own schedule.

The mirror

Bitcoiners become soldiers too. I’ve done it.

“Have fun staying poor.” Maximalism as identity. The moment Bitcoin becomes identity rather than a tool, the same trap closes. I’ve spent hours in replies that changed nothing, defending positions to people who weren’t asking.

The price is the same: wasted energy. Defense replaces building. Every hour spent dunking on nocoiners is an hour not spent making Bitcoin easier to use when they’re finally ready.

Founders do this with their companies too. The product becomes identity, and feedback starts to feel like attack. Energy goes to defense instead of iteration—and the scouts who might have found you find something else instead.

Two ways to lose: pushing against soldiers who won’t budge, or becoming one yourself.

So where does the energy go?

Not toward soldiers. That VC who dismissed you, that journalist who wrote you off—they’re not the market.

Toward the people who are ready to look. Content that answers the questions they ask when circumstances have opened them up. Products that work for their first transaction, not just their hundredth.

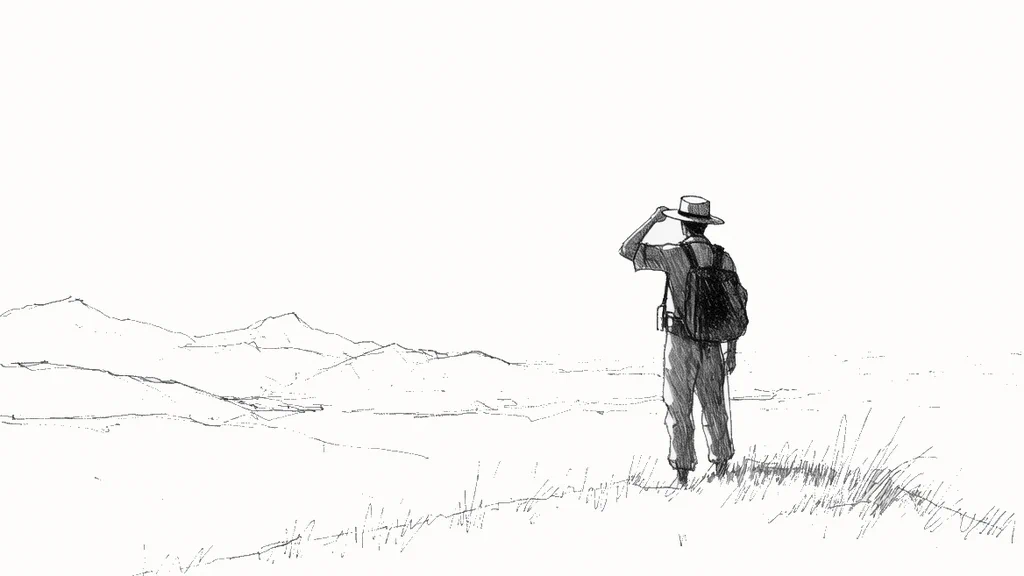

The scouts are out there. Circumstances are making more of them. The job is to be worth finding when they start looking.

That’s where the energy goes.

Thanks to Gary Krause and Trey Sellers for feedback on drafts of this essay.